INTRODUCTION

The rice harvest has very particular characteristics, such as large amount of green matter, very abrasive grain, humid and delicate, which added to the difficulties of the machinery transit due to the poor sustainability of the soil, often under conditions of high degree of humidity; make this work a more complex task than in other crops. This situation causes greater possibilities of finding high losses in the harvesting process (Miranda et al., 2002, 2003; De la Cruz et al., 2013).

In Cuba, losses during rice harvest can reach values up to 30%. It can be due to excess of weeds, action of microorganisms, split grains or very wet grains, deficiency in the planning of the harvest and different regulations of harvesters when grains are maintained with a moisture content higher than 13%, which can make the loss of whole lots (De Datta, 1986; García, 2004).

The development of the mechanization of rice harvest has had a great boom in the last 50 years. There are capitalist countries with a high degree of agricultural mechanization that have the greatest part of their agricultural areas fully mechanized, which has caused a difficult economic-social situation. However, there are still countries with a low degree of mechanization (Miranda et al., 2004, 2005; García y León, 2010; Castell et al., 2015).

Over the last few years, the collection machinery has undergone numerous technical innovations aimed mainly at increasing its work capacity. There have been several investigations related to the mechanization of the crop, harvest, maintenance of harvesters and energy cost of the mechanized harvest (Paneque and Sánchez, 2006; Paneque et al., 2009; Miranda et al., 2016; Crespo et al., 2018). The construction of a harvester is intended to produce a machine of high working capacity, versatility, great quality, comfort and easy maintenance (Miranda et al., 2003; Herrera et al., 2011). In today's world, the competitiveness of companies producing agricultural machines is growing, the trend of designers and manufacturers is to obtain harvesters with higher productivity, reliable and with a minimum use of metal, that is, more efficient machineries (Miranda et al., 2016).

In the present work, the main results and experiences obtained in the investigations carried out during the mechanized harvesting of rice in Los Palacios Agribusiness Company of Grains in the Pinar del Río Province are shown. They are stated in order to serve as a basis of the decision making for the harvest of this precious grain, given the large number of harvesters of different models that have been introduced in the country in recent years.

DEVELOPMENT OF THE TOPIC

Technologies for the Mechanized Harvesting of Rice

At the global level, there are basically two technologies for cereal harvesting: cereal harvest by phases and direct harvesting of the cereal.

The harvest of cereal by phases, as the name indicates, is carried out in two phases. The first: the phase of cutting and swathing, in which cutting platforms are used (mowing machines). The second phase is the collection, threshing and cleaning. This is done with threshing machines. This technology of harvesting is used in places where the propagation of weeds is abundant in the crop, where there are very high humidity levels, where the ripening period is not uniform and the growing season is short not allowing the grain to fully mature. Therefore, it is more effective to make the swathing of the harvested product to achieve a faster drying and its subsequent storage is appropriate.

The direct harvest of cereals is based on integrating the cutting, threshing, cleaning and delivery of the grain to the means of transport, all in a continuous technological process carried out by a harvester. For this technology, according to Griffin (1973), the recommended cutting height should maintain a grain-to-straw ratio of 1.0... 1.5, which in turn is a function of the density of plants per m2 and the humidity of the grain is around 18 to 25%. Grain losses should not exceed 4% and impurities 8% (Minag, 2014). The speed of advance must also be adjusted; normally, it is, 4.0... 5.6 km / h, depending on the conditions of the crop and the terrain. The grain loss should be less than 1%, in the cut and concave bars, respectively.

In Cuba, the direct harvesting with harvesters is generally used, but due to the soil conditions and the equipment involved in the process, different methods are used to organize it, which have been previously described by authors such as García (2004) and Miranda (2006), specifically in the conditions EAIG "Los Palacios":

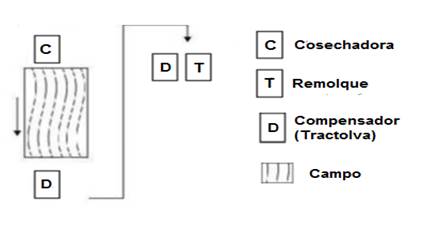

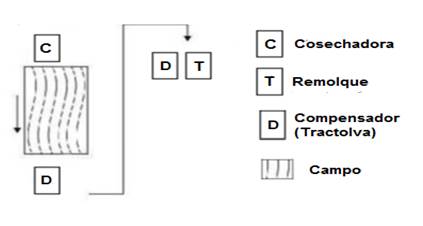

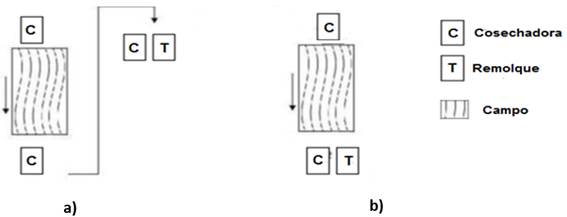

The first method is the one used in the rainy season, when the land is hydraulically saturated and it is impossible to enter the transportation means to the field in harvest, so they are used to transport the rice, self-propelled hoppers (tractolva), which use mats as a rolling element. During harvesting, the harvester stores the grain in the hopper. When the filling sensor gives the signal that, the hopper has completed its capacity, the combine stops the cut and the tractolva goes to it, to receive the harvested grain. After having completed its filling, it returns to the road or guardaraya, where the means of transport await for the delivery of the grain (Figure 1). This method has the disadvantage that the time to discharge the harvested grain to the means of transport and the time of movement of the tractolva within the field are very high, so the process is delayed.

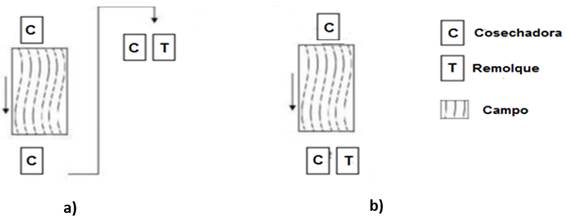

The second method is the one used when there is no tractolva and the conditions of the fields in harvest do not allow the entry of the means of transport. In this method, the harvester, after filling the hopper, interrupts the cut and goes to the head of the field where the means of transport for unloading the grain are located (Figure 2a). In this method, the harvester loses harvest time due to the delivery of the grain to the means of transport in the road. That stops the flow of the mechanized complex, since the main element of the harvest-transport process interrupts the operation to supply the means of transport the harvested grain.

The third method is used mainly during the dry season, where the soil conditions allow the transportation of the crops to the field when they are harvested. In this variant to transport the grain to the trailers, the NEWHOLLAND moving tractor on tires or other tractor whose characteristics allow it, are used. This tractor forms trains of two or three trailers that are moved to the interior of the field in harvest, placing them as close as possible to the harvesters, so that, when they are fully filled, the grain harvested can be unloaded. After the trailers are full, the moving tractor transports them to the road, where they leave them and load the rest. This operation is repeated until the train is formed of two, three or four trailers that are taken to the reception center (Figure 2b).

FIGURE 1.

Harvest method where tractolva is used. Source: Miranda (2006).

FIGURE 2.

Harvesting methods where tractolva is not used: a) in hydraulically saturated soils; b) in soils with low humidity. Source: Miranda (2006).

This method in rainy season is difficult, because the trailers are stuck, and it is difficult to haul in them by the moving tractors, this causes a great loss of time, affecting the productivity of the process.

In any of the three methods, after the trailers are placed on the road, they are hitched up to each other, to form trains of two, three and even four trailers. Then, the tractors pull these tow trains and transfer them to different drying centers of the Agroindustrial Grain Company (EAIG). They travel long distances through different vials, usually in bad conditions. In the reception center, the trailers, which are heavy, are unhitched from the tractor and are transported, one by one, to the place where the control of the quality is made and later the unloading of the grain is realized by another tractor that provides this service.

This variant of movement of the sets inside the drying centers is not feasible, because there is a loss of time in terms of transport. Therefore, it is advisable to have a moving tractor in the reception center, with the purpose of depersonalizing the tractor of its trailers, that is, the tractor arrives at the drying center, leaves the trailers full and returns with those that are empty left by another tractor (Betancourt y Bullaín, 2007).

Organization of Technical Means for Harvesting

The harvest-transport operations of rice form a productive chain, where each of its component links guarantees the correct development of the process. That makes the harvest, a complex where the interaction of each one of the elements allows the normal development of the different operations (Morejón, 2009; Iglesias et al., 2012; Morejón et al., 2012).

In Cuba, the machinery that participates in the rice harvest belongs to a specific Agroindustrial Grain Company and is grouped into mechanized complexes, which in turn make up the productive links of the harvest, an aspect that allows for better attention to the organizational, technical and technological problems that arise during the productive process.

The structure and composition of the productive link of harvest is one of the fundamental aspects that predetermine the efficiency of the technological process of the rice harvest.

Among the causes that make the post-harvest operations of rice more expensive, the transportation of the product from the field in harvest to the center of reception of the grain has a marked influence. The costs corresponding to transportation work can amount from 40 to 60% of the total costs of the harvest process. It is essentially due to the productivity of the harvester, the capacity of the means of transport, the distances to travel to the reception center, the type and conditions of the roads and the waiting times that arise during the harvest-transport-reception process. All this results in low stability of the flow of the technological process and its cost (Morejón, 2016).

For the exploitation of the harvesters and technical means involved in the rice harvesting-transport process, a group of measures prior to cutting are oriented (Ribet, 2012). They are aimed at achieving maximum use of the resources available during the rice campaign, but the exact work patterns to be followed by the harvesters are not precise, depending on the type of field. However, the diversity in the typification of rice fields affects the productivity of the system due to the differences in length and width of them, which means that greater or smaller amount of turns are made in the head of fields and, therefore, the productivity of the harvesters is affected.

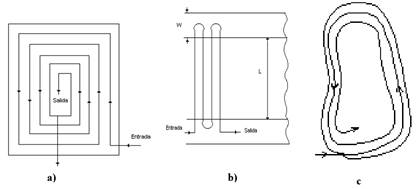

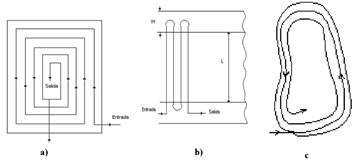

In practice, different types of turns are used, as shown in Figure 3 a, b and c. These are characterized by the length of the turn, the number of actions on the organs of direction of movement of the machine (in connecting and disconnecting clutches of lateral friction in turning the guide wheels) and by the minimum width of the swath of turns (González, 1993).

The most used turns during the rice harvest are in besanas*and circular with 900 turns in the engineering systems and 1800 in the traditional systems.

FIGURE 3.

Schemes of movement and turns of the harvesters in the rice harvest a) Circulate with turns of 900, in besanas; b and c) circulate with turns of 1800 with Shuttle and circular. Source: (González, 1993).

Determination of the Working Capacity of the Harvesters

As it is known, the prolongation of the agrotechnical periods of sowing, attention and harvest of the crops bring with them great losses in the harvest of the crops (Miranda et al., 2010a).The reduction of work periods in the field can be achieved by increasing the number of machines or increasing their productivity. Of all the points of view, the most favorable way is the second one, that is to say, by means of increasing the productivity of the machines and sets that carry out the agricultural work.

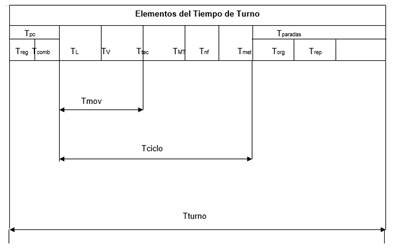

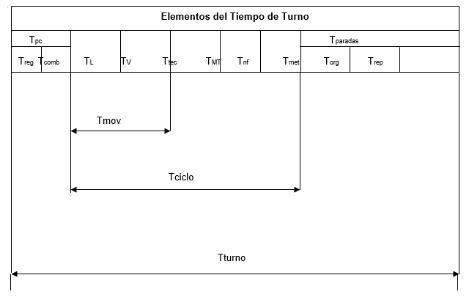

The rational use of the shift time of the machines represents a great reserve of the increase of the productivity of these. During the work of a machine or a complex of machines, the shift time is never used completely in the main or useful work, but only a part of it, the rest is lost in the displacement of the empty machines, in turns and stops for various reasons (Herrera et al., 2011; Miranda et al., 2015; Utaro, 2017).

During observation of time of the harvester, as a rule, time expenses are fixed in the following operations:

Preparatory-conclusive operations (Tpc), it includes the preparation of the machine for work and daily maintenance.

The turns and displacements with empty wagons by the field in harvest (Tmov).

The technological service in the grain delivery to the means of transport (Ttec).

Elimination of disruptions of the technological process, related to congestions of vegetable mass during the harvesting process, losses of time due to technological repairs, verification of work, etc. (Tproc).

The technical service to the machine during the work in the field, related to the elimination of small disruptions like tighten belt, chain, springs, dripping oil, fuel, etc. (Tst)

Most of the components of the shift time mentioned are casual productive functions, exploitation and other working conditions of the machine.

The general structure of the turn-time elements can be presented in the form of a diagram, Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Elements of the time of shift. Source: Miranda (2006).

Productivity of the Combine

At national and international level, many investigations have been conducted on the harvest-transport process, not only of rice cultivation, but also of other crops such as barley and sugarcane. In these crops, the technical, technological and organizational aspects and their influence on the quality and efficiency of the process have been studied (Jodosh, 1975; Jordas, 2005).

Considering the aspects pointed out by Bragachini (2000), Kiamco and Nunn (2000), Laguna (2000) and Miranda (2006), it is essential to study the productivity of the harvesters, given that they are the main link in the process under study. In addition, not only the renewal of the harvesters guarantees the efficiency of the harvest - transport process and increases the productivity of the whole system. There are other deficiencies, such as crop peaks as consequence of massive germination, coincidence of the cut-off period with the rainy season and organizational problems when using unsuitable working schemes that affect the increase in transportation cycle time. Besides, wasting time of the harvesters in carrying out maneuvers during the unloading of the harvested grain to the means of transport, deficient use of the load capacities of the means of transport, use of the working width, the speed of movement and bad conditions of the roads. Other deficiencies referred are lack of a well-founded basis for the stage of exploitation and periodicity of technical maintenance and communication problems that make the waiting time for the management and transfer of parts for the solution of failures is higher.

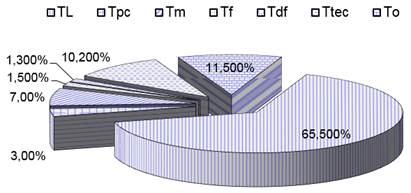

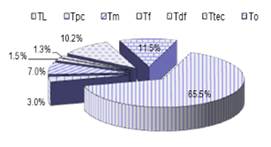

In Cuba, a research conducted by Miranda et al. (2015), showed that the use of shift time during the operation of the CLAAS DOMINATOR 130 harvester during the agrotechnical period of the rice harvest in five agricultural yields varied from 3.7 to 5.8 t / ha (see figure 5). In the observation period of 140.0 hours, 91.7 hours of clean time represented 65.5% of it. Unproductive stops due to technological breaks (Ttec) represented 10.2%. Failures (Tr) consumed 1.5% of the time, preparatory-conclusive time (Tpc) took 3.0%, technical maintenance (Tm) reached a value of 7.0%, the time for organizational stops (To) was 11.5% and the time for the realization of physiological needs and rest (Tdf) reached 1.3%.

FIGURE 5.

Behavior of the use of shift time by the combine CLAAS DOMINATOR-130. Source: Miranda et al. (2015)

Feeding the Combine

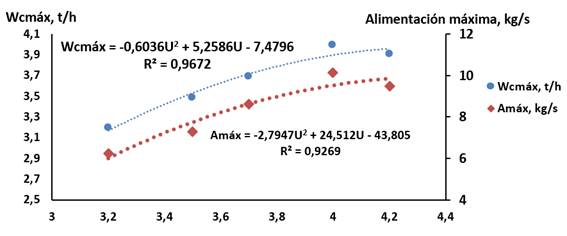

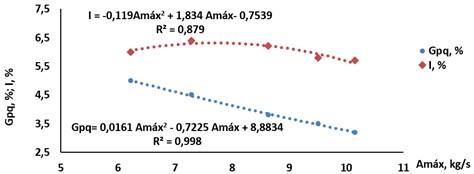

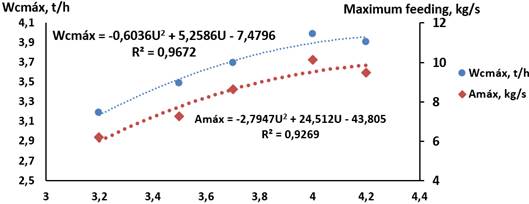

According to Morejón (2016), the real feeding of the machine is determined by the speed, the real width of work and the yield of the crop. The trend shown in Figure 6 shows the relationship that the higher the yield, the higher the maximum feed of the harvester. However, for the agricultural yield of 4 t/ha, the harvester reaches the highest feed with a value of 10.14 kg/s, observing that for higher values of feeding there are blockages in the machine and physical damage to the harvested product. This value does not depend only on the speed and the agricultural yield.

Another aspect of relevance is the use of the width of work, which was properly used in a 92.96%, because the constructive width of the harvester (Btc) is 5.40 m and a real width (Bc) of 5.02 was obtained m. The average agricultural yield of the grain taken for the calculations was 3.7 t/ha, which was the real production value. The grain content coefficient (α) reached for this yield was 0.25 and the average cut height was 27 cm.

The use of the maximum feeding of the harvester during the harvest in the agricultural yields investigated, ranged between 6.22 and 10.14 kg/s. By the obtained results, it is possible to affirm that an underutilization of the productive potentialities of the machine is evidenced.

The maximum productivity of the harvester is reached when the speed and working width of the combine are optimal (values higher than 98% of the maximum to reach) or when the speed oscillates between 4.10 and 4.20 km/h and, the working width, ranges between 5.30 and 5.40 m. This machine, in the aforementioned conditions, for agricultural yields higher than 4 t/ha should reduce the speed to avoid unnecessary technological stops due to clogging, caused by overfeeding and, in this way, preserve the quality of the harvested product, which is given by surpassing the machine design power capacity.

FIGURE 6.

Behavior of the maximum productivity (Wcmáx) and the maximum feeding (AMáx) of the NEW HOLLAND TC-57 combine depending on the agricultural yield of the harvested grain (U). Source: Morejón (2016).

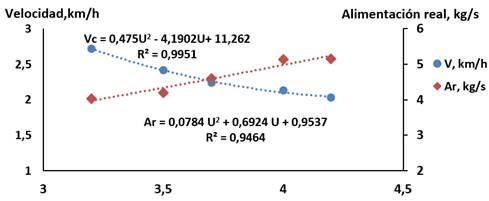

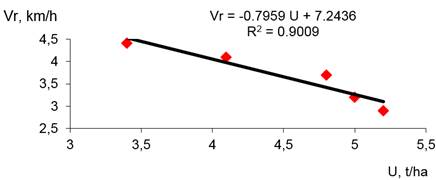

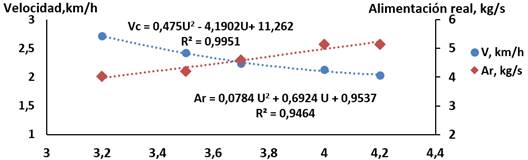

In the analysis of the real feeding in function of the speed developed by the machine in each of the agricultural performances studied, the first tends to increase without feeding blocking, because the maximum value of real feeding of the machine is 5.15 kg/s. This value is lower than the maximum potentially achievable at 4.99 kg/s, which evidences an underutilization in the feeding of the harvester, since they are no longer introduced to the cutting, threshing and cleaning systems of the machine 17.96 t/h of vegetable mass (straw + grain). This behavior is shown in Figure.7.

FIGURE 7.

Behavior of the actual speed of the harvester (Vc) and the actual feed (Ar) of the NEW HOLLAND TC-57 combine depending on the agricultural yield of the grain (U). Source: Morejón (2016)

Figures 6 and 7, indicate that when the maximum power of the harvester amounts to 10.14 kg/s and the composition values of the plant mass are optimal, the machine reaches the maximum value of productivity and quality of the harvested grain, which shows that this machine is being underused.

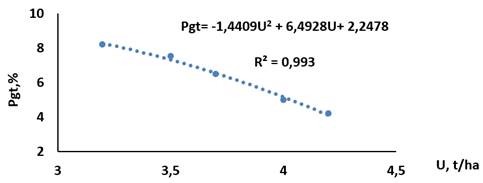

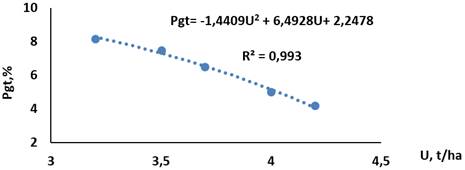

Considering the productivity and maximum feeding of the harvester for different agricultural yields, the percentage of total grain losses was determined, from the losses obtained in the cutting, threshing, separation and cleaning systems.

As it can be seen in Figure 8, for the agricultural yields studied, the percentages of total grain losses as result of the harvester range between 4.2 and 8.2%; which are in the ranges of losses (0.9... 8.5%) obtained in different crops by several authors like García (2004), Miranda et al. (2010) and Pérez et al. (2014). These percentages of losses represent a loss of grain that are between 0.18 and 0.26 t/ha. These results indicate that the correct calibration and adjustment of the grain sieves, the regulation and control of the airflow, the optimum working speed of the machine according to the agricultural performance and the experience of the operator are necessary.

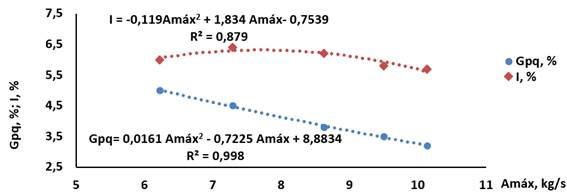

Together with these elements, it can be stated that at low feed values, the damage to the grain and the content of impurities are increased, which is given by the speed regimes developed by the machine.

FIGURE 8.

Behavior of the percentage of grain losses (Pgt) as a function of the agricultural yield of the grain (U). Source: (García, 2004).

From the above, it was found that the percentage of peeled and broken grains oscillates between 3.2 and 5% and the percentage of impurities reaches values between 5.7 and 6 (Morejón, 2016), (Figure 9). That evidenced that the percentages of losses of grains, impurities and broken grains are higher than the limits established by the Technical Instruction for Rice Cultivation (2014). Hence, the need for the harvest to be carried out in the established agrotechnical period, to control the regulations of the threshing system, specifically, the separation between the concave and the threshing drum, as well as to control the airflow in the separation and cleaning system of the grain.

FIGURE 9.

Behavior of the percentage of peeled and broken grains (Gpq) and percentage of impurities (I) as a function of the maximum power of the harvester (Amáx). Source: (Morejón, 2016).

Analyzing Figure 10, it is observed that as the maximum feeding of the harvester increases, the percentage of broken and peeled grains (Gpq) due to the machine's effect decreases, since grain damage decreases as the yield increases, which is because the straw serves as protection against the abrupt contact of the grain with the working organs.

Working Speed

As it is known, the speed of displacement of the combine harvest influences on the feeding of the combined, consequently it is necessary to establish a relation between the speed and the feeding, so that the latter is "uniform".

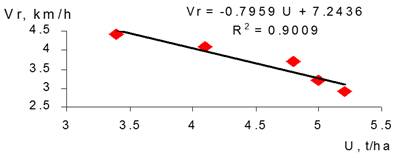

In Figure 10a, the tendency of the working speed of the harvesters is shown for the yields studied. Values between 4.41and 2.9 km/h were reached, which is lower than the recommended working speed for cereal harvesters at international level that is between 6.5 and 3 km/h. It is necessary to point out that these low speeds limit their productivity since they can not develop their feeding potential due to not being able to work at the required regimes (Miranda, 2006; Morejón, 2016).

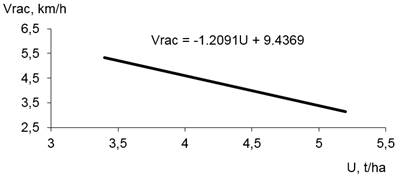

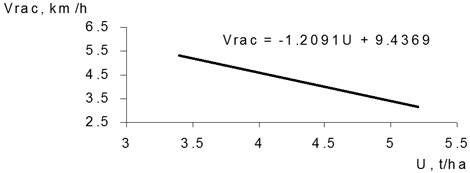

To achieve an increase in the speed of the harvesters during the harvest, it is necessary to carry out an analysis on the need to use them when the terrain conditions allow it (little rainy season), replace the mats with tire bearings (which decreases vibrations in the machines). That would enable it to reach speeds very close to those established internationally and increase productivity (Figure 10b). However, when the operator does not know the real feeding of the machine, tends to limit the speed of the same with the increase of the agricultural yield in order to avoid feeding obstruction.

FIGURE 10a.

Actual working speed (Vr) of the New Holland L-520 combine. Source: Miranda (2006).

FIGURE 10b.

Speed (Vrac) of the harvester based on the optimum feed (Ar) calculated. Source: Miranda (2006).

CONCLUSIONS

The research carried out during the mechanized harvesting of rice, as well as the results obtained in Los Palacios Agribusiness Grain Company, Pinar del Río Province, can be used for the development of efficient mechanization and serve as basis for decision making, when facing the mechanized harvest of rice and other grains in Cuba.