ORIGINAL ARTICLE

http://opn.to/a/mrFJ9

Efficiency Criteria to Evaluate Sprinkler Irrigation

Dr.C. Maiquel López-Silva [I] [*]

Dr.C. Dayma Carmenates-Hernández [I]

Dr.C. Albi Mujica-Cervantes [I]

Dr.C. Pedro Paneque-Rondon [II]

[I] Universidad

de Ciego de Ávila Máximo Gómez Baez, Facultad de Ciencias Técnicas,

Centro de Estudios Hidrotécnicos, Ciego de Ávila, Cuba.

[II] Universidad Agraria de La Habana, Facultad de Ciencias Técnicas, San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque, Cuba.

[*] Author for correspondence: Maiquel López Silva, e-mail: maiquelcuba@yahoo.com

ABSTRACT

In

this work, different efficiency criteria were proposed for the

evaluation of sprinkler irrigation. The investigation was carried out at

six central pivots of the company Cubasoy and La Cuba. The methodology

used relates the climatic, hydraulic and energy variables by means of

the consumption of the specific energy standardized in the irrigation,

in such a way that allows characterizing the systems at project and

operation level. It was determined that the specific energy to pump a

cubic meter of water ranged between 0.18 kWh·m-3 to 0.32 kWh·m-3 and the specific energy normalized in irrigation between 17.16 to 30.53 kWh·mm-1·ha-1 100-1·m-1

for application efficiencies of 77.30 to 82.80%. Energy efficiency

actually used in irrigation reached from 8.92 to 15.80% under specific

operating conditions of the system of irrigation.

Keywords:

indicators; water; energy; central pivot.

Increasing the efficiency of water and energy use in agriculture is of vital importance in the face of climate change Selim et al. (2018),

so it is necessary to generate adaptation actions that allow adjusting

planning, operation and evaluation processes of irrigation service Ojeda et al. (2012). In this context, different efficiency indicators have been proposed (De Lima et al., 2008, Rodríguez et al., 2011, Schons et al., 2012, Bolognesi et al., 2014 and Won et al., 2016),

fundamental factors to help in the decision-making process regarding

improvements in the water distribution system, in order to optimize

energy and economic consumption (Tarjuelo et al., 2015).

There

are multiple indicators of water efficiency; the most common are

irrigation efficiency and water use efficiency. Low efficiency in

irrigation systems affects agricultural yields (Camejo et al., 2017 and Zhuo and Hoekstra, 2017).

The efficiency of the sprinkler irrigation system can be evaluated by

the Uniformity Coefficient of Heerman and Hein and by the Efficiency of

Application, while the specific energy in these systems is evaluated

through specific power or consumption indicators (De Almeida et al., 2017). For example, in Brazil, they can be characterized in terms of their specific consumption between 0,2 to 0,6 kWh m3 (De Lima et al., 2008). However, they are not sufficient to characterize the overall efficiency of an irrigation system (López et al., 2017).In

this sense, the objective of this work is to analyze the efficiency

criteria for the evaluation of projects and operation of sprinkler

irrigation in the agricultural companies Cubasoy and La Cuba of various

crops, in the province of Ciego de Ávila.

The

research was carried out in the enterprises Cubasoy and La Cuba in the

hydrogeological sector south CA-II-1 and north CA-I-8, while their

average water levels behave in 9.66 m and 17.53 m, respectively,

according to the historical series of 30 years (1985 to 2015). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the central pivot irrigation system that were analyzed.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the pressure irrigation system

| Zone | Pivot | Sprinkler | Area (ha) | Topographic slope (m) | Suction pipe* | Drive pipe * | Side pipe ** |

|---|

| DN (mm) | L (m) | DN (mm) | L (m) | DN (mm) | L (m) |

|---|

| Cuba soy | 2415 | Rotator | 63,86 | 18,0 | 203,2 | 17,50 | 203,20 | 8,0 | 168,30 | 451 |

| 3120 | Rotator | 58,87 | 16,9 | 203,20 | 20,0 | 203,20 | 12,0 | 168,30 | 433 |

| 3116 | Rotator | 57,25 | 17,7 | 203,20 | 18,30 | 203,20 | 10,0 | 168,30 | 427 |

| La Cuba | Lango | Spray | 62,30 | 9,1 | 203,20 | 7,65 | 203,20 | 12,0 | 168,30 | 445 |

| Higinio | Spray | 62,50 | 9,0 | 203,20 | 8,0 | 203,20 | 31,0 | 168,30 | 446 |

| Frutero | Spray | 41,00 | 10,1 | 203,20 | 9,30 | 203,20 | 6,50 | 168,30 | 362 |

* galvanized iron; ** galvanized steel; DN nominal diameter; L length of the pipe

The

criterion of efficiency in the irrigation systems begins in determining

the minimum work to pump the water used by the crop. From the physical

criteria, the useful power for the irrigation system can be obtained

from the water level in the well and the most unfavorable point of the

irrigation area (Equation 1). While, the

powers dissipated in each of the element of the irrigation system

(suction, pump-motor, drive, sprinkler) depending on the efficiency of

application for 80% of the area properly irrigated, can be expressed by

the expressions (2; 3 and 4).

Where:

- useful power of the irrigation system (kW)

- power dissipated in the motor pump set (kW)

- power dissipated in the element (kW)

- power dissipated in the sprinklers (kW)

- manometric height of the pump (m)

-

topographic difference between the water level in the well and the

sprinkler in the most unfavorable condition of the system (m)

- flow measured at the pump outlet (m³ s-1)

- specific weight of water (9.806 kN m-³)

- efficiency of water application (%)

- the loss of load in the elements of the system (m), being the pipes and accessories

- manometric height of the sprinkler (m)

- performance of the pump-motor assembly (decimal)

The

power dissipated in the irrigation system according to the efficiency

of application for 80% of the adequately irrigated area, the geometric

slope and the load losses of the elements of the system are represented

by the following equation:

Where P

dsr

is the power dissipated in the irrigation system (kW); ∆h

s

the loss of load in the suction (m), ∆h

i

the pressure drop in the discharge pipe (m) and Δhasp the head loss in the sprinkler (m);

Criteria of Efficiency of the Irrigation System

The

efficiency criteria were based on the specific consumption of energy of

the irrigation system in accordance with the following equations:

Where:

- standardized energy consumption of the pump-motor assembly (kWh m-3 100-1 m-1)

- specific energy consumption (kWh m-3)

- consumption of useful energy (kWh ha-1)

- specific consumption in the sprinklers (kWh mm-1 ha-1)

- consumption of the specific energy normalized in the irrigation (kWh mm-1 ha-1 100-1 m-1)

- percentage of energy actually used (%)

- time it takes for the lateral to apply a watering (h)

- irrigation area of the central pivot (ha)

The

flow rate and liquid velocity in the impulse pipe was determined by

means of a PCE-TDS-100 ultrasonic meter with an accuracy of ± 1.5%. The

power in the electric motor was obtained from a MI 2392 Power Q Plus

grid analyzer with an accuracy of ± (1% + 0.5 V), ± (2% + 0.3 A), ± (3% +

3 Wh), ± 0.06 Cosine φ and ± (0.5% + 0.02 Hz). The pressure reading was

taken at the pivot, at the towers and at the end of the side by the

high precision digital manometer Type CPG1500 brand WIKA with an

accuracy of 0.05%. Climatic variables were measured from the AVM-40

Mobile Climatic Anemometer (Kestrel 4000) with an accuracy of ± 3% in

wind speed, ± 1 ° C in temperature and ± 3% relative humidity of air.

Table 2 shows the results of the

variables measured in the irrigation systems. It is observed that the

flows in the irrigation systems range between 60,10 to 76,67 L/s.

However, the manometric heights of the centrifugal pumps were superior

in the Cubasoy Company and it, consequently, reached an average

electrical consumption of 69%. The prevailing wind speeds in the central

pivots are classified as low winds according to Tarjuelo (2005),

which favorably influences an application efficiency for 80% of the

adequately irrigated area from 77,30% to 82,80%; values higher than

those reached by Román et al. (2013) and similar to those obtained by Palacios et al. (2017).

Table 2.

Measures of hydraulic, energy and climate variables

| Zone | Pivot | Hidr (L s-1 ha-1) | H

b

(m) | T

R

(h) | Pe (kW) | EA80% | Weather conditions |

|---|

| T (ºC) | HR (%) | V (m s-1) |

|---|

| Cubasoy | 2415 | 1,20 | 83,02 | 47 | 70,30 | 82,80 | 31,20 | 70,30 | 2,0 |

| 3120 | 1,23 | 86,17 | 35 | 72,0 | 80,0 | 32,40 | 63,60 | 2,77 |

| 3116 | 1,21 | 88,52 | 56 | 80 | 81,02 | 33,0 | 75,40 | 2,30 |

| La Cuba | Lango | 0,96 | 55,41 | 56 | 40,48 | 81,40 | 29,30 | 79,15 | 1,60 |

| Higinio | 1,15 | 69,92 | 68 | 69,87 | 77,30 | 30,0 | 69,50 | 2,20 |

| Frutero | 1,62 | 54,43 | 50 | 44,22 | 80,88 | 26,0 | 80,0 | 1,30 |

Hidr is the hydromodule; EA

80%

the application efficiency for 80% of the area adequately irrigated;

T the temperature; HR the relative humidity of the air and V the wind

speed.

Table 3 shows the results of the power

dissipated by each of the components of the irrigation system. It is

appreciated that the highest energy consumption in the pumping station

3116 is 19,71 kW and a power dissipated in the irrigation system of

33,03 kW, this registered the lowest efficiency of the pump set of

62,78% product to the operation time. However, the rest of the

efficiencies of the motor pump set in the other irrigation systems

ranged from 69,5 to 74,10% classified as excellent according to Abadia et al. (2008).

The favorable results were in Lango pumping station with dissipated

power of 4,37 kW and a power dissipated in the irrigation system of

17,24 kW.

Table 3.

Power dissipated by component

| Parameters | Cubasoy | La Cuba |

|---|

| 2415 | 3120 | 3116 | Lango | Higinio | Frutero |

|---|

| P

usr

(kW) | 11,16 | 9,61 | 9,77 | 4,37 | 5,34 | 5,32 |

| P

dbm

(kW) | 7,82 | 10,74 | 19,71 | 7,82 | 10,64 | 8,78 |

| P

de

(kW) | 10,98 | 9,48 | 11,11 | 7,05 | 10,68 | 7,73 |

| P

dasp

(kW) | 8,14 | 7,56 | 7,71 | 4,92 | 8,24 | 5,49 |

| P

dsr

(kW) | 28,21 | 28,73 | 33,03 | 17,24 | 28,46 | 19,63 |

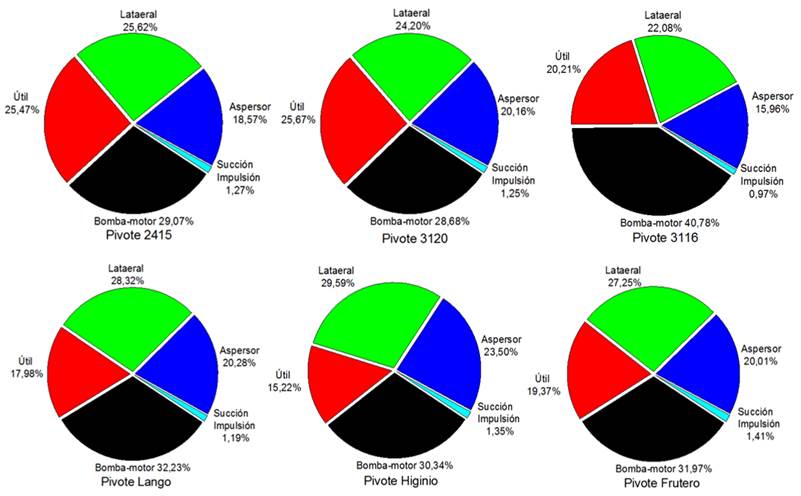

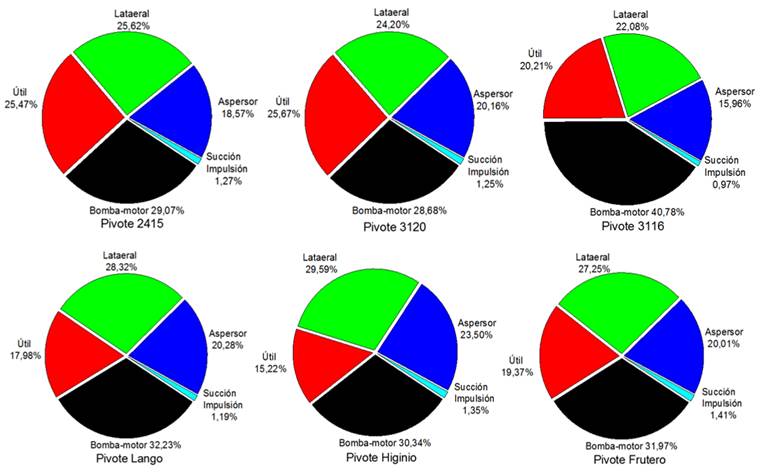

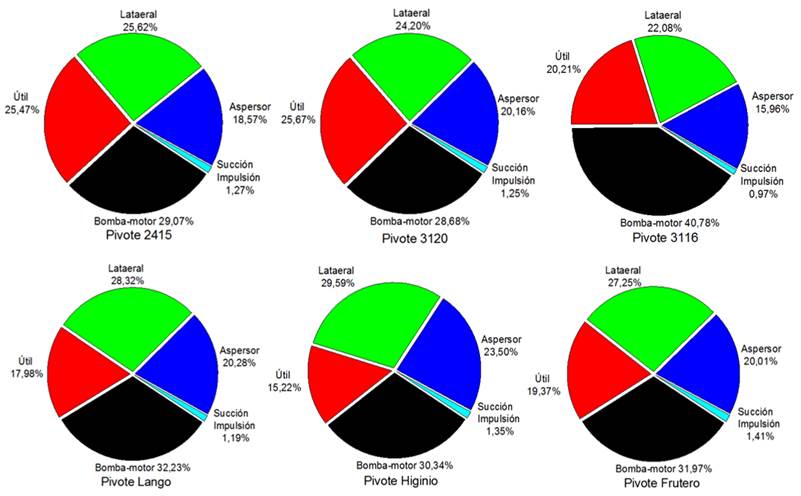

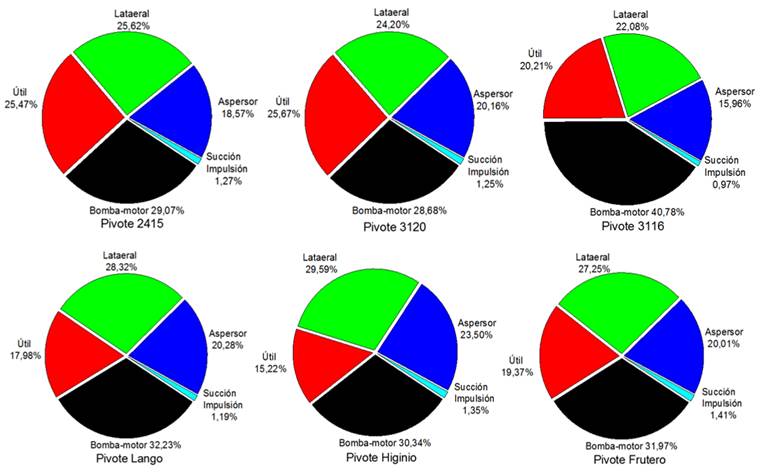

Figure 1 shows the percentages of the

power dissipated in each element of the irrigation system. It is

confirmed that the component with the highest power consumption is the

pump-motor assembly and the 3116 consumes 40,78% of its electrical

energy to convert it into energy, while the pumping station 3120 only

uses 28,68%. These obtained values are close to those reached by De Lima et al. (2008). In Figure 1,

in the laterals of the central pivots, the dissipated powers oscillate

from 24,20% to 29,59% with lengths of 309 m to 451 m. The pivot 3116,

equipped with the Rotator sprinkler, achieved a lower dissipated power

of 15,96%, which is higher than those obtained by De Lima et al. (2008),

parameter that is attributed to the years of the irrigation system in

operation without receiving adequate maintenance. However, the useful

powers of the central pivots of Cubasoy Company were superior to those

of the Cuba, because it uses the highest hydraulic variables, flow and

pump gauge height and, consequently, electrical power.

Figure 1.

Stratification of the power dissipated in irrigation systems.

The stratification of the power dissipated in

each component of the irrigation systems provides a view of the loss of

energy, but according to De Lima et al. (2008),

it is restricted because it is considered that all the water pumped is

harvested by the crop. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain indicators

expressed in terms of the efficiency of application.

Table 4 shows the results of the

hydraulic and energetic efficiency of the central pivot irrigation

system. The most favorable pivot to the consumption of useful energy was

that of Lango with 3,93 kWh ha-1 and the highest consumption

was in the pivot 3116 with 9,55 kWh ha-1 for 80% of the area adequately

irrigated at 81,40% and 81,02% of the application efficiency of the

irrigation system, respectively. However, the specific energy

consumption for pumping one cubic meter ranged from 0,18 kWh m-3 to 0.32 kWh m-3. These results are lower than those obtained by De Lima et al. (2008), Schons et al. (2012) and Brenon et al. (2018),

due to the study areas of these authors show topographic differences

greater than 20 m. However, the comparison of specific values of energy

consumption to refer to pumping stations must be made with caution

because of the different factors involved.

Table 4.

Efficiency of irrigation system

| Parameters | Cubasoy | La Cuba |

|---|

| | 2415 | 3120 | 3116 | Lango | Higinio | Frutero |

|---|

| CEN

BM

(kWh m

-3

100

-1

m

-1

) | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| CE

E

(kWh m

-3

) | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.18 |

|

CEu

80

(kWh ha

-1

) | 8.21 | 5.71 | 9.55 | 3.93 | 5.81 | 6.46 |

|

CE

Asp

(kWh mm

-1

ha

-1

) | 0.36 | 44.96 | 81.80 | 39.72 | 69.13 | 58.14 |

The pivot with the best performance of the normalized energy consumption of the pump-motor assembly was the 2415 with 0,31 kWh m-3 100-1 m-1,

which means that the operating point of the irrigation system operates

with a stable efficiency over 80%. However, it was identified that the

selection of the pump-motor assembly for the pivot 3116 was not the most

suitable, because it has the highest consumption of 0.36 kWh m-3 100-1 m-1. However, the results obtained are lower than those determined by De Lima et al. (2008) and Schons et al. (2012).

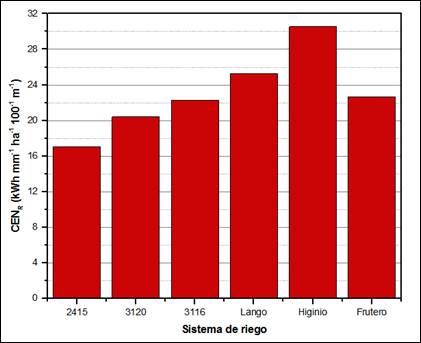

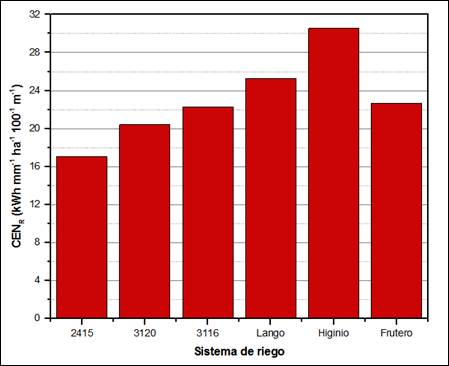

Figure 2.

Specific energy consumption normalized in irrigation.

Figure 2 shows the specific energy

consumption normalized in irrigation. It is observed that the pivot 2415

obtains the lowest specific energy consumption normalized in the

irrigation of 17.16 kWh to provide one millimeter of water in 80% of the

adequately irrigated area, when the geometric height is less than 100

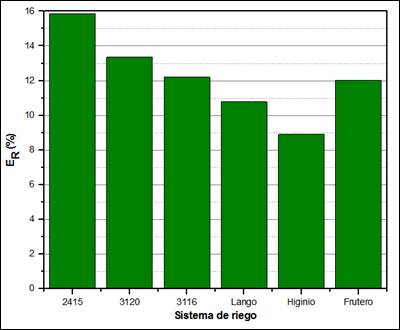

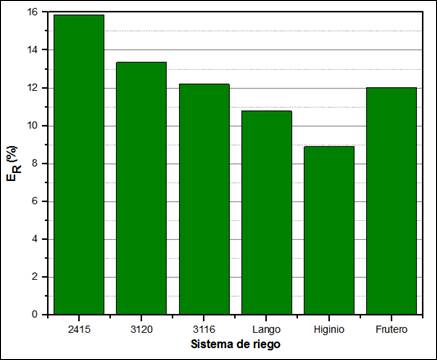

m. However, Figure 3 shows the percentage of

energy actually used and the 2415 system reaches 15.80% with a higher

percentage of energy actually used in irrigation. That means that the

pump-motor assembly, the pipes, the leakage, water losses, pressure

regulators, sprinklers and water losses due to evaporation and drag

dissipate 84.20% of the energy.

Figure 3.

Percentage of energy actually used.

In general, Figures 1 and 2

show that the central pivots of Cubasoy Company have lower specific

energy consumption and, in turn, greater energy actually used in

irrigation. This result is due to the sensitivity analysis performed to

the energy indicators that for each 1 kW of power measured in the

electric motor, the specific energy consumption normalized in irrigation

is 0,25 kWh mm-1 ha-1 100-1 m-1.

While, for every 1 m of topographic difference between the water level

in the well and the sprinkler in the most unfavorable condition of the

system, increases 0,88% the percentage of energy actually used. These

factors are also due to the characteristics of the curves of the

centrifugal pumps placed in the pressure irrigation systems.

The

stratification of the power dissipated in each component of the

irrigation system allowed identifying the pumping station with the

highest energy consumption for the immediate maintenance of its

elements. The central pivot 2415 reached the best performance of the

efficiency indicators with a normalized energy consumption of the

pump-motor set of 0,31 kWh m-3 100-1 m-1, a specific energy normalized in the irrigation of 17,16 kWh mm-1 ha-1 100-1 m-1 at an application efficiency of 82,80% for 15,80% of energy actually used in irrigation.

It

is reaffirmed that efficiency criteria contribute to the valorization

of efficient irrigation technologies for the project modality and in the

specific operation conditions for optimum crop productivity, based on a

sustainable use of natural resources; as well as it allows improving

the decision making for the previous maintenance.

Received: 23/11/2018

Accepted: 29/04/2019

Maiquel López Silva,

professor e investigador, Universidad de Ciego de Ávila Máximo Gómez

Baez, Facultad de Ciencias Técnicas, Centro de Estudios Hidrotécnicos,

Ciego de Ávila, Cuba, e-mail: maiquelcuba@yahoo.com

Dayma Carmenates Hernández,

professora e investigadora titular, Universidad de Ciego de Ávila

Máximo Gómez Baez, Facultad de Ciencias Técnicas, Centro de Estudios

Hidrotécnicos, Ciego de Ávila, Cuba, e-mail: daymas@unica.cu

Albi Mujica Cervantes,

professor e investigador titular, Universidad de Ciego de Ávila Máximo

Gómez Baez, Facultad de Ciencias Técnicas, Centro de Estudios

Hidrotécnicos, Ciego de Ávila, Cuba, e-mail: albi@unica.cu

Pedro Paneque Rondón,

Profesor e investigador titular, Universidad Agraria de La Habana,

Facultad de Ciencias Técnicas, San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque, Cuba,

e-mail: paneque@unah.edu.cu

The authors of this work declare no conflict of interest.

This article is under license Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International (CC BY-NC 4.0)

The

mention of commercial equipment marks, instruments or specific

materials obeys identification purposes, there is not any promotional

commitment related to them, neither for the authors nor for the editor.

ARTÍCULO ORIGINAL

Criterios de eficiencia para la evaluación del riego por aspersión

Dr.C. Maiquel López-Silva [I] [*]

Dr.C. Dayma Carmenates-Hernández [I]

Dr.C. Albi Mujica-Cervantes [I]

Dr.C. Pedro Paneque-Rondon [II]

[I] Universidad

de Ciego de Ávila Máximo Gómez Baez, Facultad de Ciencias Técnicas,

Centro de Estudios Hidrotécnicos, Ciego de Ávila, Cuba.

[II] Universidad Agraria de La Habana, Facultad de Ciencias Técnicas, San José de las Lajas, Mayabeque, Cuba.

[*] Autor para correspondencia: Maiquel López Silva, e-mail: maiquelcuba@yahoo.com

RESUMEN

En

este trabajo se plantearon diferentes criterios de eficiencia para la

evaluación del riego por aspersión. La investigación se realizó en 6

pivotes centrales de la empresa Cubasoy y La Cuba. La metodología

utilizada relaciona las variables climáticas, hidráulicas y energéticas

por medio del consumo de la energía específica normalizada en el riego,

de forma que permite caracterizar los sistemas a nivel de proyecto y de

explotación. Se determinó que la energía específica para bombear un

metro cubico de agua osciló entre 0,18 kWh·m-3 a 0,32 kWh·m-3 y la energía específica normalizada en el riego entre 17,16 a 30,53 kWh·mm-1·ha-1100-1·m-1

para unas eficiencias de aplicaciones de 77,30 a 82,80% y una

eficiencia de la energía realmente aprovechado en el riego de 8,92 a

15,80% en condiciones específicas de operación del sistema de riego.

Palabras clave:

indicadores; agua; energía; pivote central.

Incrementar la eficiencia del uso del agua y la energía en la agricultura es de vital importancia ante el cambio climático Selim et al. (2018),

por lo que es necesario generar acciones de adaptación que permitan

ajustar el proceso de planificación, operación y evaluación del servicio

del riego Ojeda et al. (2012). En este contexto se han propuesto diferentes indicadores de eficiencia De Lima et al. (2008); Rodríguez et al. (2011); Schons et al. (2012); Bolognesi et al. (2014); Won et al. (2016),

factores fundamentales para ayudar en el proceso de toma de decisiones

con respecto a las mejoras en el sistema de distribución de agua, a fin

de optimizar el consumo energético y económico Tarjuelo et al. (2015).

Existen

múltiples indicadores de eficiencia del agua, los más comunes son la

eficiencia del riego y la eficiencia del uso del agua. Una baja

eficiencia en los sistemas de riego afectan a los rendimientos agrícolas

Camejo et al. (2017); Zhuo y Hoekstra (2017).

La eficiencia del sistema de riego por aspersión puede ser evaluada por

el Coeficiente de Uniformidad de Heerman y Hein y por la Eficiencia de

Aplicación; mientras que, la energía específica en estos sistemas es a

través de indicadores de potencia o consumo específico De Almeida et al. (2017). Por ejemplo, en Brasil pueden ser caracterizados en cuanto a su consumo específico entre 0,2 a 0,6 kWh·m-3 (De Lima et al., 2008). Sin embargo, no son suficientes para caracterizar la eficiencia global de un sistema de riego (López et al., 2017).

En este sentido, el objetivo de este trabajo es analizar los criterios

de eficiencia para la evaluación de proyectos y operación del riego por

aspersión en la empresa agropecuaria Cubasoy y cultivos varios La Cuba

de la provincia de Ciego de Ávila.

La

investigación se desarrolló en la empresa Cubasoy y La Cuba dentro del

sector hidrogeológico sur CA-II-1 y norte CA-I-8, mientras que sus

niveles freáticos promedio se comportan en 9,66 m y 17,53 m

respectivamente, según la serie histórica de 30 años (1985 a 2015). En

la Tabla 1 se muestran las características del sistema de riego de pivote central que se analizaron.

TABLA 1.

Características del sistema de riego a presión

| Zona | Pivote | Aspersor | Área (ha) | Desnivel topográfico (m) | Tubería de succión* | Tubería de impulsión* | Tubería del lateral** |

|---|

| DN (mm) | L (m) | DN (mm) | L (m) | DN (mm) | L (m) |

|---|

| Cuba soy | 2415 | Rotator | 63,86 | 18,0 | 203,2 | 17,50 | 203,20 | 8,0 | 168,30 | 451 |

| 3120 | Rotator | 58,87 | 16,9 | 203,20 | 20,0 | 203,20 | 12,0 | 168,30 | 433 |

| 3116 | Rotator | 57,25 | 17,7 | 203,20 | 18,30 | 203,20 | 10,0 | 168,30 | 427 |

| La Cuba | Lango | Spray | 62,30 | 9,1 | 203,20 | 7,65 | 203,20 | 12,0 | 168,30 | 445 |

| Higinio | Spray | 62,50 | 9,0 | 203,20 | 8,0 | 203,20 | 31,0 | 168,30 | 446 |

| Frutero | Spray | 41,00 | 10,1 | 203,20 | 9,30 | 203,20 | 6,50 | 168,30 | 362 |

*de hierro galvanizado; ** acero galvanizado; DN el diámetro nominal; L la longitud de la tubería

El

criterio de eficiencia en los sistemas de riego inicia en determinar el

mínimo trabajo para bombear el agua utilizada por el cultivo. A partir

de los criterios físicos la potencia útil para el sistema de riego se

puede obtener a partir del nivel del agua en el pozo y el punto más

desfavorable del área de riego (ecuación 1).

Mientras que, las potencias disipadas en cada uno de los elementos del

sistema de riego (succión, bomba-motor, impulsión, aspersor) en función

de la eficiencia de aplicación para el 80% del área adecuadamente

regada, se puede expresar por las expresiones (2; 3 y 4).

donde:

- la potencia útil del sistema de riego (kW);

- la potencia disipada en el conjunto bomba motor (kW);

- la potencia disipada en el elemento (kW);

- la potencia disipada en los aspersores (kW);

- la altura manométrica de la bomba (m);

- el desnivel topográfico entre el nivel del agua en el pozo y el aspersor en la condición más desfavorable del sistema (m);

- el caudal medido a la salida de la bomba (m³·s-1);

- el peso específico del agua (9,806 kN·m-³);

- la eficiencia de aplicación del agua (%);

- la pérdida de carga en los elementos del sistema (m), siendo las tuberías y accesorios;

- altura manométrica del aspersor (m);

- es el rendimiento del conjunto bomba-motor (decimal).

La

potencia disipada en el sistema de riego en función de la eficiencia de

aplicación para el 80% del área adecuadamente regada, el desnivel

geométrico y las pérdidas de cargas de los elementos del sistema viene

representado por la siguiente ecuación:

Donde

- es la potencia disipada en el sistema de riego (kW);

- la pérdida de carga en la succión (m);

-la pérdida de carga en la tubería de impulsión (m);

- la pérdida de carga en el aspersor (m);

Criterios de eficiencia del sistema de riego

Los

criterios de eficiencia se basaron en el consumo específico de la

energía del sistema de riego conforme con las siguientes ecuaciones:

Donde:

- el consumo de energía normalizada del conjunto bomba-motor (kWh·m-3100-1·m-1);

- el consumo de la energía específica (kWh·m-3);

- el consumo de la energía útil (kWh·ha-1);

- el consumo específico en los aspersores (kWh·mm-1·ha-1);

- el consumo de la energía específica normalizada en el riego (kWh·mm-1·ha-1·100-1·m-1);

- el porcentaje de energía realmente aprovechado (%);

- el tiempo que demora el lateral en aplicar un riego (h);

- el área de riego del pivote central (ha).

Se

determinó el caudal y velocidad de líquido en la tubería de impulsión a

través del medidor ultrasónico PCE-TDS-100 con una precisión de ± 1,5%.

La potencia en el motor eléctrico se obtuvo a partir del analizador de

redes MI 2392 Power Q Plus con una precisión de ± (1% + 0,5 V), ±(2% +

0,3 A), ±(3% + 3 Wh), ±0,06 Coseno φ y ±(0,5% + 0,02 Hz). Se tomó la

lectura de presión en el pivote, en las torres y final del lateral

mediante el manómetro digital de alta precisión Tipo CPG1500 marca WIKA

con una precisión de 0,05%. Las variables climáticas se midieron a

partir del Anemómetro Climático móvil AVM-40 (Kestrel 4000) con

precisión de ±3% en la velocidad del viento, la temperatura ±1 °C y la

humedad relativa del aire ±3%.

En la Tabla 2

se muestran los resultados de las variables medidas en los sistemas de

riego. Se observa que los caudales en los sistemas de riego oscilan

entre 60,10 a 76,67 L/s. Sin embargo, las alturas manométricas de las

bombas centrífugas son superiores en la empresa Cubasoy y

consecuentemente alcanzó mayor consumo eléctrico promedio de 69%. Las

velocidades del viento predominante en los pivotes centrales se

clasifican como vientos bajos según Tarjuelo (2005),

lo que influye favorablemente en una eficiencia de aplicación para el

80% del área adecuadamente regada de 77,30% a 82,80%; valores superiores

a los alcanzados por Román et al. (2013) y similares a los obtenidos por Palacios et al. (2017).

TABLA 2.

Medidas de las variables hidráulicas, energéticas y climáticas

| Zona | Pivote | Hidr (L s-1·ha-1) | H

b

(m) | T

R

(h) | Pe (kW) | EA80% | Condiciones climáticas |

|---|

| T (ºC) | HR (%) | V (m·s-1) |

|---|

| Cubasoy | 2415 | 1,20 | 83,02 | 47 | 70,30 | 82,80 | 31,20 | 70,30 | 2,0 |

| 3120 | 1,23 | 86,17 | 35 | 72,0 | 80,0 | 32,40 | 63,60 | 2,77 |

| 3116 | 1,21 | 88,52 | 56 | 80 | 81,02 | 33,0 | 75,40 | 2,30 |

| La Cuba | Lango | 0,96 | 55,41 | 56 | 40,48 | 81,40 | 29,30 | 79,15 | 1,60 |

| Higinio | 1,15 | 69,92 | 68 | 69,87 | 77,30 | 30,0 | 69,50 | 2,20 |

| Frutero | 1,62 | 54,43 | 50 | 44,22 | 80,88 | 26,0 | 80,0 | 1,30 |

Hidr es el hidromódulo; EA

80%

la eficiencia de aplicación para el 80% del área adecuadamente

regada; T la temperatura; HR la humedad relativa del aire y V la

velocidad del viento.

En la Tabla 3 se

muestran los resultados de la potencia disipada por cada uno de los

componentes del sistema de riego. Se aprecia que el de mayor consumo

energético es la estación de bombeo 3116 es de 19,71 kW y una potencia

disipada en el sistema de riego de 33,03 kW, éste registró la menor

eficiencia del conjunto bomba motor de 62,78% producto al tiempo de

operación. No obstante, el resto de las eficiencias del conjunto bomba

motor de los demás sistemas de riego osciló de 69,5 a 74,10% clasificado

como excelente según Abadia et al. (2008).

Los resultados favorables fue la estación de bombeo de Lango con

potencia disipada de 4,37 kW y una potencia disipada en el sistema de

riego de 17,24 kW.

TABLA 3.

Potencia disipada por componente

| Parámetros | Cubasoy | La Cuba |

|---|

| 2415 | 3120 | 3116 | Lango | Higinio | Frutero |

|---|

| P

usr

(kW) | 11,16 | 9,61 | 9,77 | 4,37 | 5,34 | 5,32 |

| P

dbm

(kW) | 7,82 | 10,74 | 19,71 | 7,82 | 10,64 | 8,78 |

| P

de

(kW) | 10,98 | 9,48 | 11,11 | 7,05 | 10,68 | 7,73 |

| P

dasp

(kW) | 8,14 | 7,56 | 7,71 | 4,92 | 8,24 | 5,49 |

| P

dsr

(kW) | 28,21 | 28,73 | 33,03 | 17,24 | 28,46 | 19,63 |

En la Figura 1

se muestran los porcentajes de la potencia disipada en cada elemento del

sistema de riego. Se ratifica que el componente de mayor consumo de

potencia es el conjunto bomba-motor y el 3116 consume el 40,78% de su

energía eléctrica para convertirla en energía, mientras que, la estación

de bombeo 3120 solo emplea el 28,68%. Estos valores obtenidos son

próximos a los alcanzados por De Lima et al. (2008). En la Figura 1

los laterales de los pivotes centrales las potencias disipadas oscilan

de 24,20% a 29,59% con longitudes de 309 m a 451 m. El pivote 3116

dotado del aspersor Rotator alcanzó menor potencia disipada de 15,96%,

dicho valor es superior respecto a los obtenidos por De Lima et al. (2008),

parámetro que se le atribuye a los años del sistema de riego en

funcionamiento sin recibir el mantenimiento adecuado. Sin embargo, las

potencias útiles de los pivotes centrales de la empresa Cubasoy soy

superiores respecto a los de la Cuba, debido a que emplea las mayores

variables hidráulicas, caudal y altura manométrica de la bomba y

consecuentemente la potencia eléctrica.

FIGURA 1.

Estratificación de la potencia disipada en los sistemas de riego.

La estratificación de la potencia disipada

en cada componente de los sistemas de riego proporciona una visión de la

pérdida de energía, pero de acuerdo con De Lima et al. (2008)

queda restringido porque considera que toda el agua bombeada es

aprovechada por el cultivo, por tanto, es necesario obtener indicadores

expresados en función de la eficiencia de aplicación.

En la Tabla 4

se exponen los resultados de la eficiencia hidráulica y energética del

sistema de riego de pivote central, el pivote más favorable al consumo

de energía útil fue el de Lango con 3,93 kWh·ha-1 y el de mayor consumo el pivote 3116 con 9,55 kWh·ha-1

para el 80% del área adecuadamente regada al 81,40% y 81,02% de la

eficiencia de aplicación del sistema de riego respectivamente. Sin

embargo, los consumos de energía específica para bombear un metro cubico

oscilaron entre 0,18 kWh·m-3 a 0,32 kWh·m-3. Esto resultados son inferiores con respecto a los obtenidos por De Lima et al. (2008); Schons et al. (2012); Brenon et al. (2018),

producto a que las áreas de estudios de estos autores presentan

desniveles topográficos superiores a los 20 m. No obstante, la

comparación de valores específicos de consumo de energía para referirse a

estaciones de bombeo debe hacerse con precaución por los diferentes

factores que intervienen.

TABLA 4.

Eficiencia del sistema de riego

| Parámetros | Cubasoy | La Cuba |

|---|

| | 2415 | 3120 | 3116 | Lango | Higinio | Frutero |

|---|

| CEN

BM

(kWh·m

-3

·100

-1

·m

-1

) | 0.31 | 0.32 | 0.36 | 0.34 | 0.33 | 0.34 |

| CE

E

(kWh·m

-3

) | 0.25 | 0.28 | 0.32 | 0.19 | 0.23 | 0.18 |

|

CEu

80

(kWh·ha

-1

) | 8.21 | 5.71 | 9.55 | 3.93 | 5.81 | 6.46 |

|

CE

Asp

(kWh·mm

-1

·ha

-1

) | 0.36 | 44.96 | 81.80 | 39.72 | 69.13 | 58.14 |

El pivote con mejor desempeño del consumo de energía normalizada del conjunto bomba-motor fue el 2415 con 0,31 kWh·m-3·100-1·m-1,

lo que significa que el punto de funcionamiento del sistema de riego

opera con una eficiencia estable superior al 80%. Sin embargo, se

identificó que la selección del conjunto bomba-motor para el pivote 3116

no fue el más adecuado, porque posee el mayor consumo de 0,36 kWh·m-3·100-1·m-1. No obstante, los resultados obtenidos son inferiores a los que determinó De Lima et al. (2008); Schons et al. (2012).

En la Figura 2

se muestra el consumo de energía específica normalizada en el riego. Se

observa que el pivote 2415 obtiene el menor consumo de energía

específica normalizada en el riego de 17,16 kWh para proporcionar un

milímetro de agua en el 80% del área adecuadamente regada, cuando la

altura geométrica es inferior de 100 m. Sin embargo, en la Figura 3

se muestra el porcentaje de energía realmente aprovechado y el sistema

2415 alcanza 15,80% con mayor porcentaje de energía realmente

aprovechado en el riego; lo que significa que el 84,20% de la energía es

disipada por el conjunto bomba-motor, las tuberías, las pérdidas de

agua por fuga, los reguladores de presión, aspersores y pérdidas de agua

por evaporación y arrastre.

FIGURA 2.

Consumo de energía específica normalizada en el riego.

Figura 3.

Porcentaje de energía realmente aprovechado.

De forma general en las Figuras 1 y 2

se observa que los pivotes centrales de la empresa de Cubasoy presentan

menor consumo de energía específica y a su vez mayor energía realmente

aprovechada en el riego. Este resultado se debe al análisis de

sensibilidad realizado a los indicadores energéticos se obtuvo que por

cada 1 kW de potencia medido en el motor eléctrico el consumo de energía

específica normalizada en el riego es de 0,25 kWh·mm-1·ha-1·00-1·m-1.

Mientras que, por cada 1 m de desnivel topográfico entre el nivel del

agua en el pozo y el aspersor en la condición más desfavorable del

sistema, aumenta 0,88% el porcentaje de energía realmente aprovechado.

Estos factores también se deben a las características de las curvas de

las bombas centrífugas colocadas en los sistemas de riego a presión.

La

estratificación de la potencia disipada en cada componente del sistema

de riego permitió identificar la estación de bombeo con mayor consumo de

energía para su inmediato mantenimiento de sus elementos.

El

pivote central 2415 alcanzó el mejor desempeño de los indicadores de

eficiencia con un consumo de energía normalizada del conjunto

bomba-motor de 0,31 kWh·m-3·100-1·m-1, una energía específica normalizada en el riego de 17,16 kWh·mm-1·ha-1·100-1·m-1 a una eficiencia de aplicación de 82,80% para 15,80% de energía realmente aprovechado en el riego.

Se

reafirma que los criterios de eficiencia contribuyen a la valorización

de las tecnologías de riego eficientes para la modalidad de proyecto y

en las condiciones específicas de explotación para la óptima

productividad del cultivo, a partir de un uso sostenible de los recursos

naturales; así como permite mejorar la toma de decisión para el

mantenimiento previo.