Translate PaperORIGINAL ARTICLE http://opn.to/a/y1i9r

http://opn.to/a/y1i9rEstimation of Water Available for Plants in Cuban Soils as a Function of Prevailing Texture

[*] Correspondence to author: Greco Cid- Lazo. e-mail: dptoambiente1@iagric.cu

ABSTRACTThe objective of this work is to determine the total soil water availability and easily usable reserve for plants as a function of predominant soil texture. That will be done from information existing for the most important Cuban soils. It will be used as a tool that facilitates efficient irrigation programming. Data were available from 131 soil subtypes and 11 soil groupings, according to the database of the Agricultural Engineering Research Institute (IAgric) of Cuba. The soil depth considered was 0.5 m and a predominant particle size value was assigned to each soil profile according to its texture. Values were adjusted with a logarithmic regression analysis of the gravimetric and volumetric soil water content corresponding to the point of field capacity (Cc) and permanent wilting point (PMP). The values of the Total Available Water in the Soil (ADP) and the Easily Usable Reserve (RFU) were also quantified. The obtained relationships allow predicting in more than 90%, the variation of the limits of these soil water reserves, based on the predominant particle size in its textural composition. The ranges of variation of these limits are higher than the ranges defined at international level for silt and clay, which is associated with the characteristics of the predominant clay in many Cuban soils. The results have a high practical value as a basis for the efficient programming of crop irrigation and allow reducing the hard field and laboratory work involved in these studies.

INTRODUCTIONSoils can store different amounts of water depending mainly on their basic physical properties, like texture, structure and the content of organic matter, which influences in a particular way. The total amount of water available in the soil for plants (ADP) is the difference between the stored water at the maximum retention or storage limit known as "Field Capacity" (Cc) and the minimum storage limit, known as "Permanent Wilting Point" (PMP). Both are considered up to the depth of interest for plants or effective root depth (Zr), (Gardner, 1988; Hillel, 1998; Reichardt y Timm, 2004; U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2005; Allen et al., 2006).

A fraction of water depletion from field capacity to a point defined primarily by the characteristics of the crop, among other factors, represents the "water or reserve readily or easily available for plants" (RFU). The adequate selection of this point implies the definition of the ideal operating criterion for irrigation planning (Allen et al., 2006).

The first works carried out in Cuba on water available for plants in Cuban soils date back to the 1960s and were based on the morphological classification of soils valid in Cuba at that time. Only destructive methods of sample processing and different concepts of water retention energy in the soil were used. In this sense, the works of Nakaidze and Simeón (1972), Simeon (1979), Klimes et al. (1980) and others were important.

Later, in the decade of 1980, associated to the works for the elaboration of the map of Cuban soils, at scale 1:25 000 and to the generalized application of the irrigation forecast (Rey et al. ,1982), deeper studies were done about water availability for plants in different Cuban soils by different scientific and technical entities. The former Irrigation and Drainage Research Institute (IIRD), today, Agricultural Engineering Research Institute (IAgric), led them. These studies were made based on the current genetic classification of Cuban soils.

The continuity and updating of these studies have been carried out to date from different works of Master's and Doctorate’s thesis and national and international research projects. They have also been performed from scientific and technical services provided by researchers and specialists of IAgric to different national entities. That has generated a database with information on the physical properties of the main soil types in the country, taking into account, also, correlations with the latest Genetic Classification of Cuban soils (Cid et al., 2011).

The objective of this work is to determine the availability of total water and the reserve easily usable for plants, based on the predominant texture, as a tool that facilitates efficient irrigation programming based on the information available for the most important agricultural soils in Cuba.

METHODSDatabaseFor the research, the database of Agricultural Engineering Research Institute (IAgric) belonging to the Ministry of Agriculture of Cuba was available. Data were obtained from 131 subtypes of soils corresponding to 11 soil groupings, according to the last classification of soils valid in Cuba (Hernández et al., 2015).

The studied soils belong to the groupings: Alitic, Ferritic, Ferralitic, Fersialitic, Sialitic Brown, Sialic Humic, Vertisol, Hydromorphic, Halomorphic, Fluvisol and Histosol. Only the soils belonging to the Ferralics, Histosols, Poor Evolved and Androsols groupings of this last mentioned classification were missing.

The physical properties of the soils considered and the methods used for their determination appear in Table 1.

TABLE 1

Physical and hydrophysical properties studied and methods used

| Properties | Determination Method |

|---|

| Texture | Method of the Pipette |

| Field Capacity | Plazoleta Method |

| Permanent Wilting Point | Method of the Membrane (tension 15 atm.) |

| Bulk Density | Ring method (undisturbed samples) |

| Soil water content | Gravimetric Method |

Data ProcessingThe layer selected to carry out the studies of each soil profile was from 0 to 0.5 m, taking into account the depth reached by the roots of most of the economic important crops under irrigation in Cuba (Chaterlán et al., 2010; Zamora et al., 2014).

The data of each evaluated soil profile were organized, assigning to it a predominant particle size value and considering the established ranges for the textural classification in the Interpretation Manual of Cuban Soils (MINAG, 1984).

The intermediate values were adjusted according to a logarithmic regression analysis between the values of gravimetric moisture content corresponding to the point of field capacity (Cc) and permanent wilting point (PMP), and the predominant particle size. A similar logarithmic regression analysis was also performed for the corresponding volumetric moisture content values, calculated according to the expression (Cid et al., 2011):

Wv = Wg∙Da (1)

Where:- volumetric moisture content (cm3∙cm-3)

- gravimetric moisture content (g∙g-1)

The quality of the regressions was analyzed from the statistic Coefficient of Determination, R2.

The water depth corresponding to the upper (LSAD) and lower limits (LIAD) of the total available water in the soil for the plant (ADP) were also calculated according to Allen et al. (2006). The mean values of volumetric moisture content at field capacity WvCc and the permanent wilting point WvPMP, expressed in% of volume to the root depth of Zr = 0.5 m, were considered as follows:

Finally, the values of the Total Available Water in the Soil for the Plant (ADP) and the Easily Usable Reserve (RFU) were quantified for each profile. For the calculation of the RFU, the results of previous studies were taken into account. Those define that the maximum yields under irrigation are obtained for the treatments where soil moisture is maintained around 85% of the field capacity corresponding to 50% of the total soil water available for plants (Chaterlán et al., 2010; Zamora et al., 2014).

The calculations were performed as defined by Allen et al. (2006), from the following expressions:

ADS = LSAD - LIAD (mm) (4)

RFU = 0,5∙ADS (mm) (5)

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

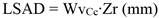

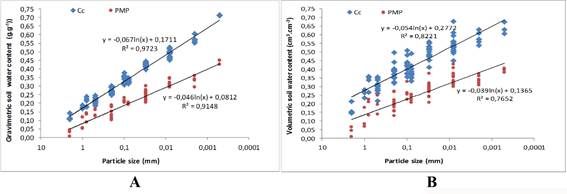

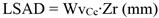

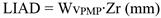

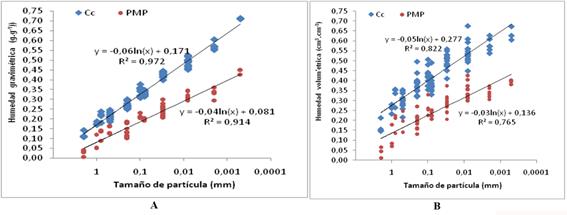

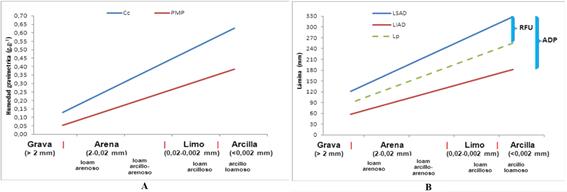

Figure 1 (A and B) shows the result of the regression analysis carried out between the values of the gravimetric and volumetric soil water content at field capacity, Cc, and permanent wilting point, PMP, and the soil predominant particle sizes.

Logarithmic equations with high values of the coefficient of determination, R2, were obtained in all cases. That makes possible to affirm that the equations defined for each case, can explain more than 95% of the variations in the gravimetric soil water content as a function of the variations of soil textures and more than 80% of the variations for the case of volumetric soil water content. The decrease of the accuracy of the regressions with the volumetric soil water content can be associated to the variability of the values of bulk density, which is not only associated to the textural changes, but to structural changes that can occur in the same type of soil (Cid et al., 2011; López et al., 2016).

It is recommended, for the practical use of these equations, to use those obtained for gravimetric soil water content and then convert the values to volumetric soil water content using the specific density data for each site.

Other authors have also pointed to the possible relationships that can be established between the variation of the size of the predominant particles in the soils that characterize their texture and the soil water content corresponding to different values of tension or hydraulic conductivity (Zotarelli et al., 2013). These relationships have been called pedotransference equations. The functions developed for European soils by Wösten et al. (1998), Jarvis et al. (2002) and Zotarelli et al. (2013) can be cited as examples.

In Cuba, Ruiz et al. (2006), define the pedotransference functions among the methods used to determine the hydraulic properties of soils. In particular, Medina et al. (2002) defined pedotransference functions to estimate the values of the water- tension curve from basic soil physical properties, but only for one type of soil (Ferrallitic).

The fundamental contribution of this work to these antecedent studies is that it involves a wide range of soil types. Besides, it allows the direct estimation of the soil water contents from a single basic soil physical property (the predominant particle size). That define the limits of the total soil water reserve available for the plants, which is essential for irrigation scheduling.

Regression curves between the soil moisture values at field capacity, Cc, and permanent wilting point, PMP, and the soil predominant particle sizes: A- for the gravimetric soil water content; B- for volumetric soil water content.

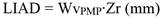

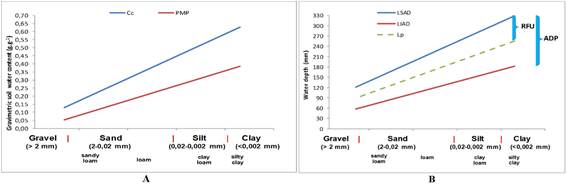

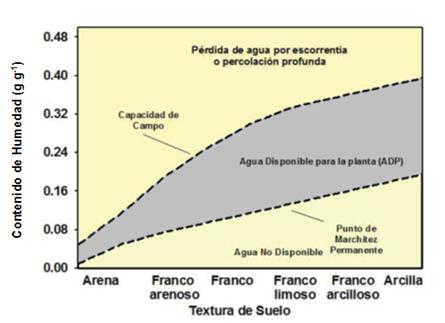

The parameters of the logarithmic equations found were used to represent the tendency of the variation in the soil water content and the water depth corresponding to the parameters that define the soil water availability for the plants, depending on the variation of the soil textural classes (Figure 2).

In this case, the different textural classes, that could be obtained from a laboratory textural analysis, have been represented, as defined in the Cuban Soil Interpretation Manual (MINAG, 1984).

These figures are useful to have a quick approximation to the values that can be expected from the soil water availability for the plants according to the soil textural classification.

A comparison of these results with the classical scheme presented by Hillel (1998), for these relationships (see Figure 3) allows us to define that the ranges of variation of soil moisture at Cc and PMP estimated for Cuban soils are higher, fundamentally for the textural classes corresponding to silt and clay. This may be associated with the characteristics of the predominant clay in many soils of Cuba that present considerable amounts of smectite and vermiculite, which causes them to tend to expand and contract according to the level of present soil moisture (Cid et al., 2004).

The results summarized in Figure 2 have an important practical value. They are a simple tool that can be used by technicians and producers to define the irrigation schedule of crops, especially, the definition of when and how much to irrigate. That would be derived from the knowledge of the predominant texture in the soil to the depth of 0.5 m, which can be defined from previous soil studies or with a specific textural analysis for the site under study.

However, for the extension of these results application in productive practice, it is necessary a strengthening of the soil textural analysis, that is carried out in different laboratories of the country, by different entities, so that the predominant particle size can be more accurately specified. In this sense, it is recommended to use a weighted average of the particle size, taking into account the percentage of particles present in each textural fraction.

Variation trend of parametres that define soil water availability for plants as a soil texture: A- for gravimetric soil moisture; B- for water depth.

Recommendations for its Practical Implementation

Take advantage of the potential that is available from international projects and national programs to strengthen the textural analysis of soil laboratories and other entities of the agriculture system.

Train technical personnel directly related to soil and irrigation activity in the production base for the practical use of these relationships.

Use the relationships obtained as part of the tools included in the Irrigation Advisory Services and, in particular, for irrigation forecasting.

Perform field validations of these relationships, based on monitoring soil water content in control fields, using current easy-to-use techniques such as electromagnetic probes (TDR).

CONCLUSIONS

The relationships determined for the most important agricultural soils of Cuba, make it possible to predict, with an accuracy of more than 95%, the variation of the limits of the total soil water reserves and easily usable reserves for the plants based on the predominant particle size in their textural composition.

The ranges of variation of soil moisture to field capacity, Cc and permanent wilting point, PMP, estimated for Cuban soils, are higher than the ranges defined by international studies, fundamentally for the textural classes corresponding to silt and clay, which is associated with the characteristics of the predominant clay in many Cuban soils.

The results obtained have a high practical value as a basis for the efficient irrigation programming of crops and allow reducing the hard field and laboratory work involved in these studies, as well as to promote more precise planning of water resources available for irrigation.

INTRODUCCIÓNLos suelos pueden almacenar diferente cantidad de agua dependiendo fundamentalmente de sus propiedades físicas básicas que son la textura y la estructura, y en ello también influye de manera particular el contenido de materia orgánica. La cantidad total de agua disponible en el suelo para las plantas (ADP) es la diferencia entre las láminas de agua almacenadas al límite máximo de retención o almacenamiento conocido como “Capacidad de Campo” (Cc) y el límite mínimo de almacenamiento, denominado como “Punto de Marchitez Permanente” (PMP), ambas consideradas hasta la profundidad de interés para las plantas o profundidad radical efectiva (Zr) (Gardner, 1988; Hillel, 1998; Reichardt y Timm, 2004; U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2005; Allen et al., 2006).

Una fracción de agotamiento del agua desde la capacidad de campo hasta un punto definido fundamentalmente por las características del cultivo, entre otros factores, representa el “agua o reserva fácilmente disponible para las plantas” (RFU). La adecuada selección de este punto implica la definición del criterio operativo ideal para la planificación del riego (Allen et al., 2006).

Los primeros trabajos realizados en Cuba sobre el agua disponible para las plantas en los suelos cubanos se remontan a la década de 1960 y tuvieron como base la clasificación morfológica de los suelos vigente en Cuba en esos momentos. Se utilizaron solo métodos destructivos de procesamiento de muestras y diferentes conceptos de energía de retención del agua en el suelo. En este sentido se destacan los trabajos de Nakaidze y Simeón (1972); Simeon (1979); Klimes et al. (1980) y otros.

Posteriormente en la década de 1980, asociados a los trabajos para la confección del mapa de suelos de Cuba a escala 1:25 000 y a la aplicación generalizada del pronóstico del riego Rey et al. (1982), se realizaron estudios más profundos de la disponibilidad del agua para las plantas en diferentes suelos cubanos, donde participaron diferentes entidades científicas y técnicas del país liderados por el antiguo Instituto de Investigaciones de Riego y Drenaje (IIRD), hoy Instituto de Investigaciones de Ingeniería Agrícola (IAgric). Estos estudios se hicieron tomando como base la Clasificación Genética de los suelos cubanos vigente

La continuidad y actualización de esos estudios se ha venido realizando hasta la fecha a partir de diferentes trabajos de tesis de maestría, doctorado y proyectos de investigación nacionales e internacionales, así como servicios científico técnicos prestados por investigadores y especialistas del IAgric a diferentes entidades del país, lo que ha generado una base de datos con información de propiedades físicas de los principales tipos de suelos del país, teniendo en cuenta además correlaciones con la última clasificación genética de los suelos cubanos (Cid et al., 2011).

El objetivo del presente trabajo consiste en determinar a partir de la información disponible para los suelos de mayor importancia agrícola de Cuba, la disponibilidad del agua total y la reserva fácilmente utilizable para las plantas en función de la textura predominante, como herramienta que facilite la programación eficiente del riego.

METODOSBases de DatosPara la investigación se dispuso de la base de datos con que cuenta el Instituto de Investigaciones de Ingeniería Agrícola (IAgric) del Ministerio de la Agricultura de Cuba.

Se obtuvieron datos de 131 subtipos de suelos pertenecientes a 11 agrupamientos, según la última clasificación de suelos vigente en Cuba (Hernández et al., 2015). Los suelos estudiados pertenecen a los agrupamientos: Alíticos, Ferrítico, Ferralítico, Fersialítico, Pardo Sialítico, Húmico Sialítico, Vertisol, Hidromórfico, Halomórfico, Fluvisol e Histosol. Solo faltaron suelos pertenecientes a los Agrupamientos Ferrálicos, Histosoles, Poco Evulucionados y Antrosoles de esta última clasificación mencionada.

Las propiedades físicas de los suelos consideradas y los métodos empleados para su determinación aparecen en la Tabla 1.

TABLA 1

Propiedades físicas e hidrofísicas estudiadas y métodos utilizados

| Propiedades | Método de determinación |

|---|

| Textura | Método de la pipeta |

| Capacidad de Campo | Método de la plazoleta |

| Punto de Marchitez Permanente | Método de la membrana (tensión 15 atm.) |

| Densidad Aparente | Método del anillo (muestras inalteradas) |

| Humedad del suelo | Gravimétrico |

Procesamiento de los datosLa capa seleccionada para realizar los estudios de cada perfil de suelo fue de 0 hasta 0,5 m, teniendo en cuenta la profundidad que alcanzan las raíces de la mayoría de los cultivos de importancia económica bajo regadío en Cuba (Chaterlán et al., 2010; Zamora et al., 2014).

Se organizaron los datos de cada perfil de suelo evaluado asignando al mismo un valor de tamaño de partícula predominante y considerando los rangos establecidos para la clasificación textural en el manual de interpretación de los suelos cubanos (MINAG, 1984).

Los valores intermedios se ajustaron según un análisis de regresión logarítmica entre los valores de humedad gravimétrica correspondientes al punto de capacidad de campo (Cc) y punto de marchitez permanente (PMP), y el tamaño de partícula predominante.

Un análisis de regresión logarítmica similar se realizó también para los valores de humedad volumétrica correspondientes, calculados según la expresión (Cid et al., 2011):

Wv = Wg∙Da (1)

donde:- humedad volumétrica (cm3∙cm-3)

- humedad graviemtrica (g∙g-1)

- densidad aparente (g∙cm-3).

La calidad de las regresiones se analizó a partir del estadígrafo Coeficiente de Determinación, R

2

.

Se calcularon además las láminas correspondientes a los límites superior (LSAD) e inferior (LIAD) del Agua total Disponible en el Suelo para la Planta (ADP), según lo definido por Allen et al. (2006), considerando los valores medios de humedad volumétrica a capacidad de campo WvCc y al punto de marchitez permanente WvPMP, expresados en porcentaje (%) de volumen hasta la profundidad radical de Zr= 0,5 m, como sigue:

Por último se cuantificaron para cada perfil los valores del Agua total Disponible en el Suelo para la Planta (ADP), y la Reserva Fácilmente Utilizable (RFU). Para el cálculo de la RFU se tuvo en cuenta los resultados de estudios antecedentes que definen que los máximos rendimientos bajo riego se obtienen para los tratamientos donde se mantiene la humedad alrededor del 85% de la capacidad de campo que se corresponde con el 50% de la humedad aprovechable en el suelo (Chaterlán et al., 2010; Zamora et al., 2014).

Los cálculos se realizaron según lo definido por (Allen et al., 2006), a partir de las expresiones siguientes:

ADS = LSAD - LIAD (mm) (4)

RFU = 0,5∙ADS (mm) (5)

RESULTADOS Y DISCUSIÓNEn la Figura 1 (A y B) se presenta el resultado del análisis de regresión efectuado entre los valores de las humedades gravimétrica y volumétrica a capacidad de campo, Cc, y punto de marchitez permanente, PMP, y los tamaños de partículas predominantes en el suelo.

Como se puede apreciar se obtuvieron en todos los casos ecuaciones logarítmicas con altos valores del coeficiente de determinación R2, lo que permite afirmar que las ecuaciones definidas para cada caso permiten explicar más del 95% de las variaciones en la humedad gravimétrica en función de las variaciones texturales del suelo y más del 80% de las variaciones para el caso de la humedad volumétrica.

La disminución de la precisión de las regresiones con las humedades volumétricas se puede asociar a la variabilidad de los valores de densidad aparente, que no solo está asociada a los cambios texturales sino a cambios estructurales que se puedan dar en un mismo tipo de suelo (Cid et al., 2011; López et al., 2016).

Se recomienda para el uso práctico de estas ecuaciones utilizar las obtenidas para la humedad gravimétrica y convertir después los valores a humedades volumétricas utilizando los datos de densidad aparente específicos para cada sitio.

Otros autores también han apuntado a las posibles relaciones que pueden establecerse entre la variación del tamaño de las partículas predominantes en los suelos que caracterizan su textura y las humedades correspondientes a distintos valores de tensión o la conductividad hidráulica. A estas relaciones se les ha denominado ecuaciones de pedotransferencia y pueden citarse como ejemplos las funciones desarrolladas para suelos europeos por Wösten et al. (1998); Jarvis et al. (2002) y Zotarelli et al. (2013).

En Cuba, Ruiz et al. (2006), definen las funciones de pedotransferencia entre los métodos empleados para determinar las propiedades hidráulicas de los suelos. En particular Medina et al. (2002) definieron funciones de pedo transferencia para estimar los valores de la curva tensión-humedad a partir de propiedades físicas básicas, pero solo para un tipo de suelo (Ferralítico).

El aporte fundamental de este trabajo a esos estudios antecedentes está fundamentalmente en que involucra un rango amplio de tipos de suelos y que permite la estimación directa a partir de una sola propiedad física básica del suelo (el tamaño de partícula predominante), de las humedades que definen los límites de la reserva de agua total disponible en el suelo para las plantas, importantes para la programación del riego.

Relaciones encontradas entre los valores de humedad a capacidad de campo, Cc, y punto de marchitez permanente, PMP, y los tamaños de partículas predominantes en el suelo: A- para las humedades gravimétricas; B- para las humedades volumétricas.

Los parámetros de las ecuaciones logarítmicas encontradas se utilizaron para representar la tendencia de la variación de las humedades y las láminas de agua correspondientes a los parámetros que definen la disponibilidad del agua para las plantas, en función de la variación de las clases texturales de los suelos (Figura 2).

En este caso se han representado las distintas clases texturales que pudieran tenerse de un análisis textural de laboratorio, según lo definido en el Manual de interpretación de los suelos cubanos (MINAG, 1984).

Estas figuras resultan útiles para tener una aproximación rápida a los valores que pueden esperarse de la disponibilidad del agua para las plantas según la clasificación textural del suelo.

Una comparación de este resultado con el esquema clásico presentado por Hillel (1998), para estas relaciones (ver Figura 3) permite definir que los rangos de variación de las humedades a Cc y PMP estimados para los suelos cubanos son superiores, fundamentalmente para las clases texturales correspondientes al limo y la arcilla. Esto puede estar asociado a las características de la arcilla predominante en muchos suelos de Cuba que presentan cantidades considerables de smectita y vermiculita lo que hace que tiendan a dilatarse y contraerse de acuerdo al nivel de humedad presente (Cid et al., 2004).

Los resultados resumidos en la Figura 2 tienen un valor práctico importante ya que resultan una herramienta simple que puede ser utilizada por técnicos y productores para la definición de la programación del riego de los cultivos, sobre todo la definición del cuándo y cuánto regar, a partir del conocimiento de la textura predominante en el suelo hasta la profundidad de 0,5 m, lo cual puede ser definido a partir de estudios de suelos anteriores o precisado con un análisis textural especifico para el sitio en estudio.

No obstante, estos resultados imponen para la extensión de su aplicación en la práctica productiva, de un fortalecimiento del análisis textural del suelo que se realiza en diferentes laboratorios del país por diferentes entidades, para que pueda ser precisado con mayor exactitud el tamaño de partícula predominante. En este sentido se recomienda usar un promedio ponderado del tamaño de partícula teniendo en cuenta los porcientos de partículas presentes en cada fracción textural.

Tendencia de la variación de los parámetros que definen la disponibilidad del agua para las plantas en función de la textura del suelo: A- expresados en humedades gravimétricas; B- expresados en láminas de agua

.

Recomendaciones para su implementación práctica

Aprovechar las potencialidades que se tienen a partir de proyectos internacionales y programas nacionales para fortalecer los análisis texturales de los laboratorios de suelo y de otras entidades del sistema.

Capacitar al personal técnico directamente relacionado con la actividad de suelo y riego en la base productiva para el uso práctico de estas relaciones.

Utilizar las relaciones obtenidas como parte de las herramientas incluidas y los Servicios de Asesoramiento a Regantes y en particular para el pronóstico del riego.

Realizar validaciones de campo de estas relaciones a partir del seguimiento de la humedad del suelo en campos controles utilizando técnicas actuales de fácil utilización como las sondas electromagnéticas (TDR).

CONCLUSIONES

Las relaciones determinadas para los suelos de mayor importancia agrícola de Cuba permiten predecir con una precisión de más del 95%, la variación de los límites de las reservas de agua total y fácilmente utilizable para las plantas en función del tamaño de partícula predominante en su composición textural.

Los rangos de variación de las humedades a capacidad de campo, Cc y punto de marchitez permanente, PMP, estimados para los suelos cubanos son superiores a los rangos definidos por estudios a nivel internacional, fundamentalmente para las clases texturales correspondientes al limo y la arcilla, lo que se asocia a las características de la arcilla predominante en muchos suelos cubanos.

Los resultados obtenidos tienen un alto valor práctico como base para la programación eficiente del riego de los cultivos y permiten disminuir el engorroso trabajo de campo y laboratorio que implican estos estudios así como pueden tributar a la planificación más precisa de los recursos hídricos que dispone el país para la irrigación.